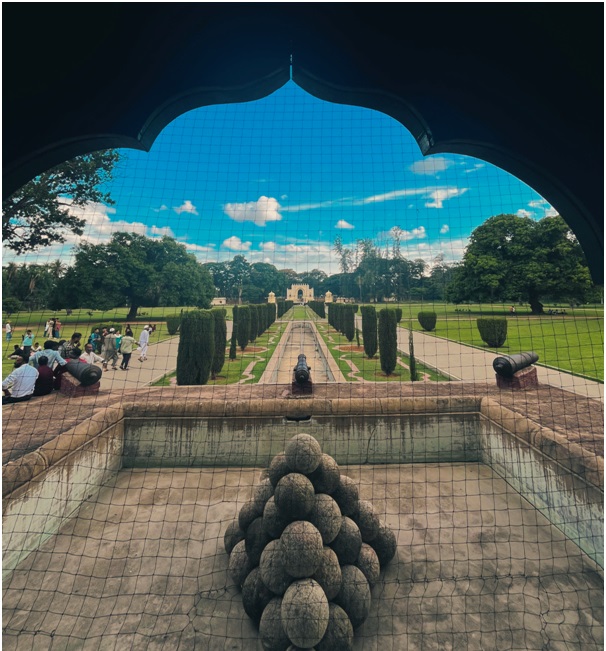

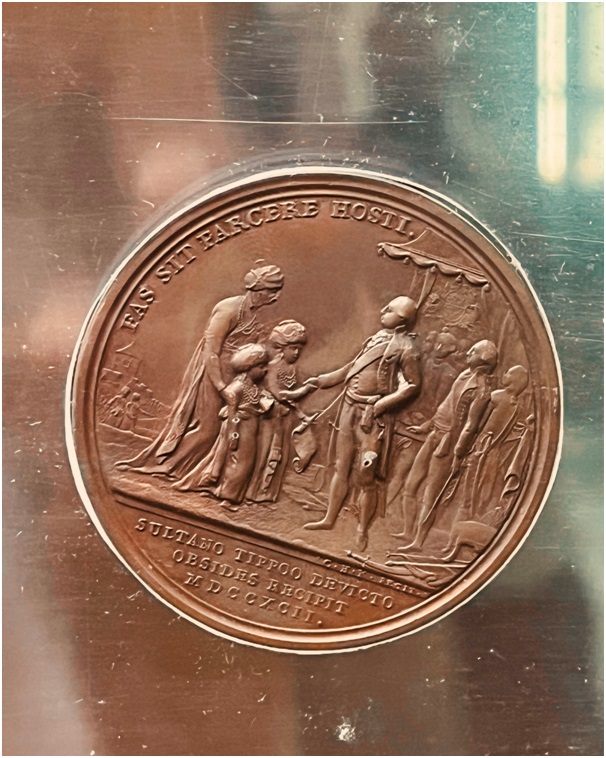

During my Mysore trip, I returned to my residence, the Mysore Palace, I couldn’t help but ponder the fate of Tipu Sultan’s wealth and family after his tragic death. The stories of looting following his fall at Srirangapatnam haunted me. I vividly imagined the scene: a British soldier finding Tipu, semi-conscious, eyes greedily on his diamond-studded belt or gem-encrusted dagger. The chaos of that moment—no one knows who fired the fatal shot—marked the beginning of Mysore’s decline from a grand empire to a looted shell. Treasures, including a life-sized gold-encrusted tiger, were lost to history, and the reported looted wealth, then worth millions of pounds (now equivalent to billions of US dollars), highlighted a significant drain of wealth from India to Britain. And Lord Cornwallis who lost the American Revolution War to George Washington, suddenly became hero defending Tipu Sultan.

Tipu’s family was forcibly removed from Mysore, their wealth meticulously cataloged and transported under British supervision. I was struck by the role of Augustus Andrews, who safeguarded Tipu’s jewels, including the treasures of Tipu’s eldest daughter, Shahzadi Noorunnissa Begum. Twenty years later, it reportedly still took six bullock carts to transport the jewels, including diamonds, pearls, rubies, emeralds, ivory, and clothing, from Mysore to Calcutta. Andrews, though not a looter, amassed considerable wealth from these ventures, using it to build one of Bath’s grandest houses, now the Macdonald Bath Spa Hotel with a restaurant named Vellore—a nod to where Tipu’s family was first exiled.

During a London visit, I stood before items that once belonged to Tipu Sultan, now scattered across museums worldwide, like the Victoria and Albert Museum. I marveled at a life-sized wooden toy tiger from around 1793, still capable of producing a growling roar. These symbols of Tipu’s power and pride, now far from their original home, continue to mesmerize millions of visitors. Yet, it is hard to reconcile how such potent symbols of resistance and sovereignty ended up in foreign hands, becoming mere curiosities for tourists.

In my reflection, Tipu Sultan’s legacy resonates profoundly today. His famous octagonal tiger throne, we ith eight tiger heads but never used, symbolized his royal power. The Huma bird, a symbol of emperorship, once perched atop the throne, now resides in the Royal Collection Trust at Windsor Castle. One of the tiger heads from the throne is displayed at the Clive Museum in Powis Castle, Wales, while another was hidden away for a century in Featherstone Castle, Northumberland. These relics, once symbols of Tipu’s might, now scattered and isolated, reflect the fragmented legacy of a once-great ruler.

In Calcutta, where Tipu’s descendants were relocated, the remnants of his empire are stark. Late Asok Roy from Bengal Jewellery acquired Tipu Sultan’s father Haider Ali’s Takti or Tabeez (amulet) in the early 1990s, which later resurfaced at a 2017 exhibition in Paris, organized by the Al Thani Collection of Qatar. Tipu’s descendants, like his fourth son Sultan Muhinuddin, were documented living in Calcutta, far removed from the grandeur of their ancestor’s reign. Some of his descendants live humble lives today, as rickshaw pullers, electricians, or tailors, yet they remain proud of their heritage. Every year on November 20, they celebrate Tipu’s birthday, keeping his memory alive amidst a drastically changed world.

During my Calcutta visits, I often reflect on this legacy. I walk through Ballygunge, where once, a dry path connected Sunny Park and Queens Park to Tipu Sultan’s family hunting lodge, now an apartment building. It’s surreal to think this unassuming path was once trodden by a legend’s family members. The Tollygunge Club, with one of the oldest golfing ranges outside Scotland, is another site rich in history. Here, I dined at the Tipu Sultan restaurant, a place that subtly pays homage to the past while serving the present and also reminds us the political injustices his family faced.

My Calcutta journey remains incomplete without a visit to Chowringhee and a Gin & Tonic at The Oberoi Grand Hotel’s Chowringhee Bar. Watching the crowds near the Tipu Sultan Shahi Masjid, built by Prince Golam Mohammed, a son of Tipu, I reflect on the irony of sipping a British colonial drink, Gin & Tonic, while contemplating Tipu’s legacy. The story of how British soldiers in India turned the bitter quinine, used to combat malaria, into a refreshing drink by adding gin and tonic water, adds a layer of complexity to the colonial narrative.

The jewels looted from Tipu’s treasury sparked immense public interest in Britain, influencing poets, fiction writers, and artists such as Charles Dickens, J.M.W. Turner, and John Keats. Some of Tipu’s items have been documented by scholars like D. Alexander in *The Arts of War* and M. Jasanoff in *Edge of Empire: Conquest and Collecting in the East*. These works ensure that future generations can admire and study the remnants of a great Indian culture.

In the Chowringhee Bar, surrounded by East India Company paintings, I am struck by the irony of how Tipu Sultan’s legacy is remembered today. His story and treasures, once symbols of resistance, are now displayed as part of a rich cultural heritage that continues to captivate people across the globe. Yet, for those who honor his indomitable spirit, Tipu Sultan’s legacy is far more than just the jewels and artifacts—it is a testament to resilience, resistance, and the enduring struggle for sovereignty.

Expanding on these reflections, one can’t help but see Tipu Sultan’s legacy as a complex narrative of power, loss, and cultural survival. His story is a poignant reminder of the consequences of imperialism, where the wealth of nations was not only plundered but also recontextualized within the very cultures that sought to subdue them. Tipu’s treasures, now housed in foreign lands, continue to evoke admiration and curiosity, but they also serve as silent witnesses to a history of resistance and the ultimate costs of conquest in the Indian subcontinent by greedy East India Company . As his legacy endures, it does so not just in the museums and collections but in the hearts of those who remember and honor his indomitable spirit.